|

"We used to say we were dropping a Cadillac," -- retired U.S. Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Dean Failor.

The basic operational concept for laser guidance and targeting

from a combat aircraft was simple. The Weapons System Operator would use a laser marking device mounted on the back-seat canopy of one F-4 to illuminate that target. Another F-4 loaded with the laser

guided bombs would make the attack dive bomb run. Depending on fuel loads, the Phantom could carry two 2,000 pound guided bombs. The number was fewer because the fixed guidance fins on the bomb only

allowed one bomb per station on the fighter. In later versions of the Paveway bomb, folding rear fins allowed for two bombs to be loaded on aircraft bomb station hardpoints.

Later in the Vietnam  War fighters used pods and could designate their own targets or a target for a flight of F-4s, but even the buddy system, which put two aircraft at risk instead of one, was deemed so

accurate by the Air Force it went into combat trials and was later dubbed the Pave Light system (PAVE is an acronym for Precision Avionics Vectoring Equipment) when the back-seat illumination routine was used

in combat. Later, Pave Knife pods, the primitive precursor to current day targeting pods, were carried by a single F-4 in a two or four ship flight. The pods allowed one aircrew to

illuminate a target and several to drop their guided bombs on it. War fighters used pods and could designate their own targets or a target for a flight of F-4s, but even the buddy system, which put two aircraft at risk instead of one, was deemed so

accurate by the Air Force it went into combat trials and was later dubbed the Pave Light system (PAVE is an acronym for Precision Avionics Vectoring Equipment) when the back-seat illumination routine was used

in combat. Later, Pave Knife pods, the primitive precursor to current day targeting pods, were carried by a single F-4 in a two or four ship flight. The pods allowed one aircrew to

illuminate a target and several to drop their guided bombs on it.

This was a particularly useful tactic for well protected, sturdy bridges. By summer 1973, just before airstrike operations

from bases in Thailand were canceled, F-4s were equipped with the more advanced Pave Spike pod which featured a television-laser combination tracking and targeting system, a

bomb release computer and an easy access cockpit mounted control panel. The pod, which resembled a long tube with a big bulging bulb on the forward end, was mounted on one of

the Phantom's centerline Sparrow missile wells. This freed up a wing station for more ordnance.

After initial test practice runs for aircrews, the bombs were

easy to use, unlike the complicated optical glide bombs and missiles of th e day. More importantly to the Air Force, the bombs not only came within the thirty foot target designation, they were cheap. When compared to other "precision"

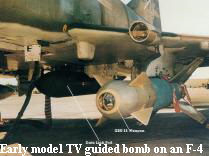

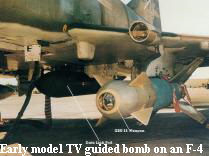

guided weapons at the time, Paveway I was a frugal investment. The GBU-8 television guided bombs which had a higher failure rate, cost the government around $17,000, but the initial Paveway bombs

were priced at around $4,000, Word remembers, and as the production lines geared up near the end of the Vietnam War the bomb prices had dropped to $2,000 a copy. e day. More importantly to the Air Force, the bombs not only came within the thirty foot target designation, they were cheap. When compared to other "precision"

guided weapons at the time, Paveway I was a frugal investment. The GBU-8 television guided bombs which had a higher failure rate, cost the government around $17,000, but the initial Paveway bombs

were priced at around $4,000, Word remembers, and as the production lines geared up near the end of the Vietnam War the bomb prices had dropped to $2,000 a copy.

Compared to the pay stub of a young Air Force officer of the time, though, the bombs were deemed expensive, but the aircrews wouldn't have traded them for the bomb's weight in

gold in combat. "We used to say we were dropping a Cadillac," retired U.S. Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Dean Failor recalled. "They were very accurate, and I guess compared to

other munitions of the time cheap, but to us 'Crew Dogs' they were Cadillacs. They were worth a Cadillac too, because they worked. We really didn't like the electo-optical guided bombs

because they didn't always work." Failor was a WSO who used laser guided bombs from 1970-1973 in tours of duty in Southeast Asia including the Linebacker I and II campaigns.

The bombs were used for more that just dropping bridges, Failor said. "They were very versatile. We used them for cutting road junctions along the (Ho Chi Mihn) Trail, hitting bulldozers, just  about all hardened targets and even

destroying tanks," Failor recalled. "I remember one bulldozer we hit that had been hidden in a bomb crater at a difficult angle (to strike). We put the laser guided bomb right on it, and the dozer just started

tumbling end over end." about all hardened targets and even

destroying tanks," Failor recalled. "I remember one bulldozer we hit that had been hidden in a bomb crater at a difficult angle (to strike). We put the laser guided bomb right on it, and the dozer just started

tumbling end over end."

Within Texas Instruments there was a lot of hoopla surrounding Paveway bombing accuracy, Tom Weaver thought. "A lot of people say those

bombs were coming within seven to ten feet of the target. I don't think we ever got them that close, but we sure got them within the 30-foot range," Weaver said.

Although very accurate, Paveway bombs were not magic bullets. Launch parameters, which pilots call a "basket," had to be followed or the bombs would not guide. The release

parameters were much the same as dive bombing -- roll in on the target around 20,000 feet, acquire the target and release the bomb at about 10,000 feet. The laser guidance allowed

the pilots to pull out the desired 10,000 foot altitude mark, largely above the bulk of the deadly ground fire. "You had to be good at what you were doing," Failor said. "There's no

doubt about that. There had to be cooperation between the guy in back and the pilot and a general understanding of how the bomb worked. Once you got that down, though, it went

well. When you used it properly the laser guided bomb was so much better than a regular iron bomb that there is just no comparison."

Drawbacks to the weapons usage were cloudy weather, and

also haze and smoke from previous bomb runs could pose a problem. The first Paveway systems had no night time capability. Even with the drawbacks, though, the bombs

racked up a 68-percent kill record. By the end of the conflict in Vietnam, the Air Force had used more that 25,000 laser guided bomb units, and 17,000 had been judged successful. |

|

War fighters used pods and could designate their own targets or a target for a flight of F-4s, but even the buddy system, which put two aircraft at risk instead of one, was deemed so

accurate by the Air Force it went into combat trials and was later dubbed the Pave Light system (PAVE is an acronym for Precision Avionics Vectoring Equipment) when the back-seat illumination routine was used

in combat. Later, Pave Knife pods, the primitive precursor to current day targeting pods, were carried by a single F-4 in a two or four ship flight. The pods allowed one aircrew to

illuminate a target and several to drop their guided bombs on it.

War fighters used pods and could designate their own targets or a target for a flight of F-4s, but even the buddy system, which put two aircraft at risk instead of one, was deemed so

accurate by the Air Force it went into combat trials and was later dubbed the Pave Light system (PAVE is an acronym for Precision Avionics Vectoring Equipment) when the back-seat illumination routine was used

in combat. Later, Pave Knife pods, the primitive precursor to current day targeting pods, were carried by a single F-4 in a two or four ship flight. The pods allowed one aircrew to

illuminate a target and several to drop their guided bombs on it.  e day. More importantly to the Air Force, the bombs not only came within the thirty foot target designation, they were cheap. When compared to other "precision"

guided weapons at the time, Paveway I was a frugal investment. The GBU-8 television guided bombs which had a higher failure rate, cost the government around $17,000, but the initial Paveway bombs

were priced at around $4,000, Word remembers, and as the production lines geared up near the end of the Vietnam War the bomb prices had dropped to $2,000 a copy.

e day. More importantly to the Air Force, the bombs not only came within the thirty foot target designation, they were cheap. When compared to other "precision"

guided weapons at the time, Paveway I was a frugal investment. The GBU-8 television guided bombs which had a higher failure rate, cost the government around $17,000, but the initial Paveway bombs

were priced at around $4,000, Word remembers, and as the production lines geared up near the end of the Vietnam War the bomb prices had dropped to $2,000 a copy. about all hardened targets and even

destroying tanks," Failor recalled. "I remember one bulldozer we hit that had been hidden in a bomb crater at a difficult angle (to strike). We put the laser guided bomb right on it, and the dozer just started

tumbling end over end."

about all hardened targets and even

destroying tanks," Failor recalled. "I remember one bulldozer we hit that had been hidden in a bomb crater at a difficult angle (to strike). We put the laser guided bomb right on it, and the dozer just started

tumbling end over end."