|

"It was just a bunch of junk ..."

-- Weldon Word The Army passed on the idea of a laser guided Shrike, but the idea of using a laser didn't die with the theoretical laser

guided Shrike missile. A few engineers at Texas Instruments saw laser guidance as a viable, low cost and ultimately light weight approach to guiding a bomb or maybe an artillery shell.

Laser light is able to project a spot over great distances and the beam of light stays tight. Unlike a flashlight beam shined into the trees on a dark night. the laser beam doesn't scatter light

particles. Because the beam stayed tight, Word felt he could use it as information to guide a weapon. Just after working on the Shrike study, While working on TI systems at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, Word

discussed the issue of bomb accuracy with U.S . Air Force Colonel Joe Davis who as the deputy base commander was in charge of weapons ranges at Eglin. . Air Force Colonel Joe Davis who as the deputy base commander was in charge of weapons ranges at Eglin.

"Joe wanted to find a way to help our guys over in Southeast Asia get their bombs right on the target. Now, he wasn't in the bomb development business, but Joe knew there was a problem, and he wanted

to find and answer," Word said.

Blazing through heavy ground fire and flak was normal for most bomb runs throughout Southeast Asia. Many World War II veterans

who flew in the war remembered the flak being more intense in some spots of North Vietnam than it had been in heavily defended sections of Germany two decades earlier. Since most

aircrews didn't want to end up with jets shattered by exploding anti aircraft fire, they jinked to avoid it, thus spoiling the aim of their bombs.

Pulling out a picture of the Than Hoa Bridge out of a desk

drawer, the Eglin colonel showed Word where the problem was, Word remembers. "I started counting craters in that photo. I stopped when I got to 800 or so, and I never did

finish." Davis told Word he wanted a weapon that could be released around 10,000 feet and then "fly" the rest of the way to the target with a large enough warhead that one or two

bombs would destroy even the hardiest of targets. Giving the issue some thought, Word and other engineers at TI figured a beam of laser light could be used as a bomb guidance system.

The Shrike studies had been promising, but when the TI engineers broached the idea with anybody at Eglin but Colonel Davis it was as if a Hollywood producer had walked into the

room wanting to make a teleplay out of the latest science fiction novel. "They would just laugh at us and think we were nuts," Word recalled. There were those within TI who thought

lasers were a far fetched dream, too. "Many people just thought it was crazy. There were a lot of detractors -- military and within TI -- who said this can't be done," TI engineer Nick Baker said.

A few months after seeing the photo of the Than Hoa Bridge, Word had almost given up on using a laser guidance system when Davis stoked again the fires of development.

"On a Friday morning in early June of '65, we mentioned to Joe Davis that no one else at Eglin feels the Air Force has a bombing problem," Word recalls. "Col. Joe explodes. Then

he says, 'Have a proposal on my desk by 8 a.m. Monday and I will fund it. It has to be for a dozen guided bombs that have a thirty foot delivery accuracy and, of by the way, it needs to be

fixed price for less than $100,000 and the schedule has to be six months for delivery and flight test.' "

Over that weekend the Word embarked on a marathon,

sleepless 72-hour development session. By Monday, the end result was an 18-page hand written proposal for a laser guided bomb development program which he felt could deliver a

bomb that could come within thirty feet of a target; the program was projected to cost $99,000, with a six month delivery schedule. "Later it turned out to be nothing like what

we produced. I mean we just had a seeker device basically nailed onto a stabilizer. There was no way it would have flown," Word said. "It was just a bunch of junk, but that's

where we laid the ground work was in that original proposal."

Word made the deadline, and while he waited on the Eglin military and civilian officials to butt heads over his proposal,

the Texas Instruments engineer grabbed a six pack of beer and headed to the nearest beach. "We were told to get lost for a few hours, so I headed to the beach," he said. On paper, the

concept was convincing to Colonel Joe Davis who sent the proposal straight to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio, home of Air Force research and development projects. Within

a few days, the idea made its way to the Limited Warfare Office at Wright Patterson and landed on director Jack Short's desk. The office had a program where defense contractors

could come up with ideas for improved weapons or war material such as better tent pegs, ponchos or radio equipment. A good idea would net a company $100,000 in seed, or

development, money and if it worked maybe a lucrative government contract to build the product.

After a severe lobbying campaign from Davis and Word, the

office signed off on the project, giving the TI team $100,000 in development funds. The team had six months to develop a device which for the military would change the way bombing

accuracy was defined. Their task was to get the bomb within 30 feet of the target. This would beat the average bomb accuracy of the day, which ranged from 100-1,000 feet

depending on the tactics, the target and the weather.

"I don't think we knew what we were building at first -- not in terms of the scope of the program. Certainly, we didn't

envision this would become what it has today in terms of accuracy and reliability, " Nick Baker offered. "We just wanted to find a way to guide a bomb. Nobody really thought it would

be as accurate as it was."

"It was unlike any other development

program anyone had ever seen,"

-- Weldon Word A

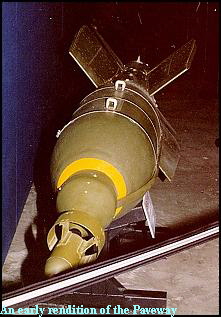

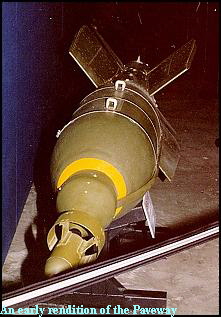

lthough the bomb may appear simple in design today -- bolt a guidance seeker on the front and control fins on the rear of a standard bomb casing -- in the fall of 1965 it was

anything but easy. Word and his fellow engineers identified the problems they would have to conquer in a short time. First, the team had to develop and build a seeker which would

sense the laser light, and then figure a way to move that information to the Shrike control unit bolted on the end of the bomb. Finally, they had to make it fly -- the bomb had to be aerodynamic.

"It was unlike any other development program anyone had ever seen," Word says today. "We had so little time and there was a heck of a lot of improvising. One problem would crop

up, we would solve it, and then another three would be waiting. You had to move fast."

Most of the work was adapting and improving missile technology, but Tom Weaver remembered one of the most significant challenges the TI team faced

was electronically moving the guidance data from the seeker to the control unit in an era of transistors and circuit breadboards. "We faced the problem that this had never

been tried before. It wasn't so much (developing) the laser, as it was working with that slow data rate we had to guide on. It was only like eight or ten pulses per

second. And as far as data rates go that's very slow when you are talking about a bomb falling through the air to a target some 6,000 to 8,000 feet away," Weaver said. "That data rate

problem was one of the biggest challenges to get past." The team finally locked in 10 pulses per second as the golden number for a bomb to guide to the target.

Working out of TI's labs in Dallas, Texas, and trudging down to the steamy, jungle like ranges of Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, the team set about to make laser guided bombs a

reality in September 1965. With only six months to design, test and prove laser guidance, the pressure of the ticking clock brought on a fast paced, sometimes unorthodox development

cycle for the guided bomb. The TI engineers didn't know how to use a laser, having never seen a working model. Salonimer loaned them a laser, one of only two in the world, and they

used the water tower in Plano, Texas as a fixed object to measure laser light return. |

|