|

Building the better bomb:

The development of Laser Guided

Munitions

By Shelby G. Spires

Locked away in an archive, a 1965 aerial

photograph tells the story of a thousand misses, a thousand sorties and a

thousand personal stories of horror in the quest to drop the Ham Rung, or

Dragon's Jaw, Bridge in Than Hoa, North Vietnam. At the height of the Vietnam

War, the bridge stood defiantly against the technological might of a nation

which could orbit spaceships around the earth, but could not manage to bullseye

a bomb on a French built bridge 10,000 miles away in Southeast Asia.

The

stark black and white photo shows a bridge, a river and thousands of water

filled craters in the ground -- missed bombs -- made in the attempt to drop the

bridge. The effort had been costly in terms of aircrews and aircraft lost, and

yet the Dragon's Jaw, as bridge was nicknamed, still remained open to traffic.

The bridge was one of hundreds of targets over Southeast Asia which were either

too well defended to bomb accurately or protected by Washington due to fears

over civilian deaths that may result from a stray bomb.

The problems

weren't due to any lack of effort on the part of American aircrews in 1965. That

the North Vietnamese prison were quickly filling up with pilots, navigators and

weapons system operators, attest to their courage. Difficulties with bombing

were quickly identified from Thailand to Washington, aircrews flying sorties

over Southeast Asia didn't have the proper tools for the job.

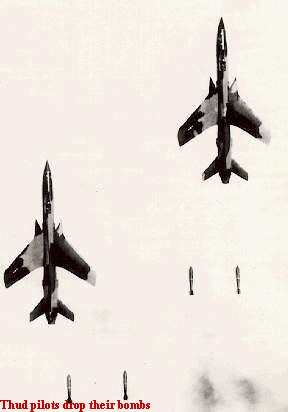

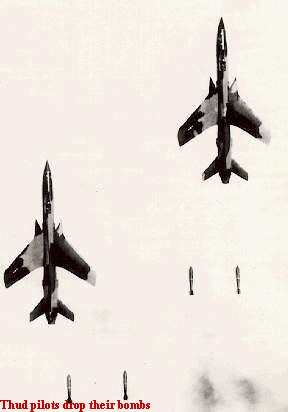

F-105

"Thunderchief" pilot Nick Lacey knew there was a problem. He flew a

fighter-bomber designed for nuclear strike against targets in Europe, but used

it as the backbone of the American strategy to attack targets in the jungles and

plains of Southeast Asia. Loaded up with fat World War II iron bombs, Lacey

flew the F-105 on strikes against well protected, entrenched targets during

Operation Rolling Thunder -- the three year bombing campaign designed to force

the North Vietnamese to the peace table.

"For what it was designed for

'The Thud' was a great aircraft. Get low, fly in below the enemies defenses and

loft a bomb -- an atomic bomb more than likely -- and leave the area. But for

dive bombing small targets like trucks and even bridges in Vietnam ... it was

difficult. It just wasn't designed for that," the retired Air Force colonel

said . .

The accuracy problems cost the American military

in the terms of dead and imprisoned aircrews and lost aircraft, but it also

created the vicious circle of overkill. Because leaders in Washington couldn't

be certain a target had been destroyed, they required multiple sorties back to

the same place to expend ordnance on phantom structures. "I remember going back

to targets in North Vietnam a few times to drop bombs on something that wasn't

there. Light, shadows and angle of sight had created an illusion on photo

reconnaissance that there was something left, and there was nothing there. We

were just going up north for no reason," Lacey said. "We had to face the

(Surface-to-Air-Missiles) and ground fire all over again for a target that

probably had been obliterated days before."

The military needed a weapon

to keep airmen out of range of ground fire and one accurate enough to cut out

needless trips back to a target which was already destroyed. The need was a

precision guided munition which was safe, cheap and easy to use.

Leaders

in the Pentagon had a problem of their own, one of denial. It would take a

Texas Instruments engineer, a laser light scientist in Alabama, a head strong

Air Force colonel in Florida and a lot of crazy ideas to convince Washington

that American aircrews couldn't hit a bullseye with their bombs and a solution

was needed.

"The Air Force didn't have a bombing problem. Or that's what

they would tell you. It was all bureaucratic stuff. The guys over there

dropping the bombs knew there was a bombing problem, and people here in the

states knew there was a bombing problem. But trying to fix it meant admitting

there was a problem. It was crazy," the man who headed the development team of

the first effective laser guided munition Weldon Word said. "I remember one

colonel I was with saying 'The Air Force doesn't have a bombing problem. Let me

tell you what we did 15 years ago, in Korea. There all you had to do was tell

me which railroad ties you wanted our bombs to be placed on and we would go up

and do it. That was in Korea. Think how much better we are now.' They had

lost I don't know how many airplanes trying to drop the Than Hoa bridge. The

Air Force had a bombing problem, but for whatever reasons they wouldn't admit

it."

Continue to "The Early Work"

|

|